After widespread criticism of campus police departments and calls for reform, colleges and universities are supplementing departments with mental health counselors.

Increasingly aware of the toll the past two years of political and pandemic-related upheaval have taken on student mental health, college administrators are seeking to provide better support by establishing crisis response teams and adding trained counselors to campus police departments.

California State University, Long Beach, recently created a mobile crisis unit staffed with mental health counselors instead of police to respond to student mental health crises. Other universities, including Oregon State University and several University of California campuses, are also developing mobile response teams that are attached to campus police departments but led by trained therapists. At the University of Florida, a mental health professional now accompanies campus police officers when they respond to calls about a student in crisis. At the University of Mary Washington, in Virginia, students will have access to counseling support after business hours to reduce the decision-making role of police during such crises.

These shifts on college campuses come as demand for mental health care continues to soar among students feeling emotionally battered by the police killing of George Floyd—and the wave of angry national protests that followed—and the deadly COVID-19 pandemic.

Both events had deep repercussions on college campuses that continue to play out today. Students across the country have called on university administrators to substantially defund or abolish campus police departments, citing concerns about aggressive policing and racial profiling, as well as the mishandling of students experiencing mental health crises. The sudden shift to remote education triggered by the pandemic also revealed deep social and financial inequities among students and exacerbated existing concerns about student mental health.

“Mental health concerns have now become one of the top few priorities for institutions in a way that you just didn’t see—I think student affairs professionals would say it was 15 years ago, but not presidents, and now presidents are saying it,” said Juliette Landphair, vice president of student affairs at Mary Washington, who chaired a working group last summer on the university’s response to mental health crises, which led to the after-hours counseling support and other changes.

A New Service

The mental health working group was formed following a lengthy review of the campus police force, which was prompted by the department’s decision to help local Fredericksburg police manage off-campus protests related to Floyd’s murder. Fredericksburg police used tear gas to disperse the downtown crowd, where the presence of campus police angered students, alumni and community members. Some student activists called for the university to defund the campus police department.

They weren’t alone in making such demands; students at other campuses across the country have voiced similar sentiments.

Some university leaders, including University of Minnesota president Joan Gabel, responded by cutting ties with local police departments. Johns Hopkins University paused a plan to create its own police force, though that has recently resumed. In a 2021 campus safety plan drafted in response to student and faculty calls for reform, the University of California system recommended that each campus create a multidisciplinary crisis team to respond to behavioral health crises, among other tasks.

Troy D. Paino, president of the University of Mary Washington, responded to the demands on his campus by forming a community advisory panel to review the downtown protest and recommend reforms. The panel suggested, among other things, revising the crisis response protocol to make a mental health professional the primary responder and making counselors available 24-7 to students, which could reduce the need to call campus police.

Starting this academic year, Mary Washington is contracting with Protocall, a mental health company and on-call counseling service that gives students another place to turn when there’s a crisis, particularly after business hours.

Landphair said the university doesn’t have the staffing capacity to start its own crisis response team to meet the needs of its 4,000 students.

Even with Protocall on board, how campus officials and students respond to a situation should depend on the type of crisis, she said; if a student is experiencing suicidal ideation, for instance, the police should be called. But the Protocall service could be a good resource for students having a panic attack or feeling so depressed that they haven’t gotten out of bed for several days, she said.

Landphair expects the app to launch on campus in mid-September and is curious to see how it’s used.

“It’s a lot about recognizing the reality of our mental health challenges right now and to acknowledge that we’re listening to students,” she said. “I think just knowing that there are resources available in and of itself is valuable.”

Landphair said campus police leaders supported the change. She believes it will give officers more time to focus on community policing and building trust with students as well as with the broader community.

“They’re not mental health clinicians; they are police officers,” she said.

John Ojeisekhoba, chief of police at Biola University and president of the International Association of Campus Law Enforcement Administrators, says collaboration between mental health professionals and campus public safety officials is “a phenomenal approach,” but he doesn’t believe campus cops should be completely removed from responding to mental health crises.

“The majority of campus law enforcement or campus public safety departments operate 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days of the year, and have a unique role to play to support and care for students on our campuses needing support,” he wrote in an email. “Because of this, we are concerned about removing campus law enforcement or campus public safety departments from any process where the risk to the safety of the student is present and would be counterproductive. Working together is vital.”

He noted that the IACLEA has been training campus police on student mental health issues and working with mental health professionals to develop best practices for years.

“Although 2020 elevated the discussion about this mostly at the municipal policing level, solution-based partnerships on this subject on campuses have been taking place even before the 2020 protests,” he wrote.

Dylan Rodríguez, a professor in the department of media and cultural studies at the University of California, Riverside, and a member of the UC Cops Off Campus Coalition, said universities were already planning to hire more mental health professionals prior to the protests, a move he called “the lowest-hanging fruit” for university administrators.

“One of the most repetitive patterns of police violence, including fatal police violence, has been their response to people having mental health crises,” he said. “The police are not trained to actually care for people. That’s not what they do. And universities know that this is a major liability and a major public relations scandal all the time.”

UC Riverside recently announced changes to its police department, including a new team of behavioral and mental health professionals who will be first responders to calls involving students in crisis. Sworn officers will be available for calls involving threats to the campus, according to a news release.

Rodríguez said he’s heard from students, faculty and staff who plan to avoid the new team altogether because they are worried about the connection between the mental health workers and police departments.

“They are going to have a lot of trouble earning the trust of people in mental health crises,” he said of the new mental health workers. “This paradigm of tethering mental health care responses to police power is really distressing to people.”

A Co-Responder Model

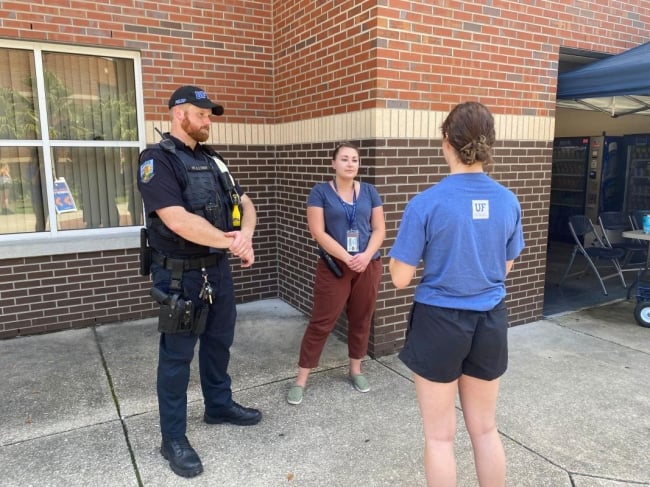

University of Florida administrators decided on a co-responder model to help address mental health needs on campus. The model pairs a mental health professional with a university police officer to respond to a mental health emergency on campus.

“A lot of these things aren’t crimes that law enforcement across the country are getting called to,” said Meggen Sixbey, assistant director of the behavioral services division in the University of Florida Police Department. But there’s often no one else available to handle such calls, she said.

Sixbey said the university’s model gives the responding officer and counselor flexibility in deciding how to best handle a situation. For example, the counselor might take the lead on a well-being check, but if they go on a call about a potentially suicidal individual who could be armed, the officer would take the lead.

Sixbey previously worked as a crisis counselor in the university’s counseling center and moved to the police department to start the co-responder model.

She said UFPD is the first campus police department in the country to launch this type of co-responder program, which builds on the department’s previous collaboration with campus mental health partners. The University of Florida’s police department has been a national law enforcement mental health learning site for the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance since 2010.

What a program looks like depends on a specific campus’s needs, she said. She’s heard from several universities that want to expand the role of counselors in responding to mental health crises.

“If we can really try to flesh those out some, we can just do better by our campuses, because we know there’s so much trauma associated with arrests and hospitalizations and a lot of times they are not necessary,” she said.

The co-responder or mental health counselor in the University of Florida’s model is an employee of the campus police department and started working with the department in July. A second clinician is scheduled to start within the next month. Sixbey said her goal is to have a 24-7 operation.

Mobile Crisis Units

At Cal State Long Beach, two mental health professionals are working out of the campus police station and are available to respond instead of a police officer to a psychiatric crisis or emergency—a change that’s part of the university’s broader mental health overhaul.

The Mobile Crisis Unit launched earlier this summer with the help of a $400,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Beth Lesen, vice president of student affairs at CSULB, said the decision to create the unit was “a no-brainer.”

“The police wanted it; the students wanted it,” she said. “People don’t want armed police officers responding to noncriminal emergencies if they can avoid it, especially communities of color.”

She noted that students of color had advocated for the change.

“Our communities have been clear that they don’t want to meet with the police unless there was a crime that happened,” she said. “We heard them and moved as quickly as we could to fix that and make sure they didn’t have to.”

When Lesen started at Cal State Long Beach in June 2020, setting up the mobile crisis unit was one of her first projects. She and other administrators consulted with several Los Angeles–area precincts to determine the best way to set up the unit, ultimately deciding to station the mental health counselors in the police department. That decision also allows the mobile crisis unit to respond to calls through the police dispatch units, which Lesen said was necessary to avoid confusing callers by requiring them to use a number other than 9-1-1.

Lesen said the university had to hire the two counselors, train them and develop new protocols to start the unit, which would have been difficult to do without the support of the campus police department.

“This is something that the police department has been asking for for a while,” she said. “They knew that it would be a big asset to the campus. I was the one who went slow on it, because we needed to do it correctly.”

The unit’s first full academic year begins this month, and Lesen will monitor the number of calls and outcomes of the responses, such as whether a student is hospitalized or referred for counseling.

“This should make more of our students feel comfortable in making a call if they need help,” she said.

This article originally appeared on InsideHigherEd.com